Based on an interview with Shigeo Takdeda,

President and CEO of wooden wheel manufacturer Takeda Building Contractor`s Office

A look back through history shows evidence of wheel production and use from ancient times. In Japan, wooden wheel production techniques are said to have been developed during the Asuka Period (538-710) , and artisans who continue to use these techniques can still be found in Kyoto. Extraordinarily enough, the original wheel structure and production process remain virtually unchanged, allowing the techniques of old to live on in the wooden wheels of hoko and other traditional parade floats used in Japanese festivals. To learn more about these Asuka-period techniques and the art of producing wooden wheels, we visited the Takeda Building Contractor's Office in Kyoto's Fushimi Ward.

One of the Greatest Inventions of the Human Race, the Wheel First Appeared in Japan during the Asuka Period

The wheel is an object with a circular frame that is used to facilitate the transport of other objects. Wheels utilize the principle that rolling friction is much lower than sliding friction. Wheels not only allow vehicles to accelerate forward, but also make the basic functions of turning and stopping possible, and it can safely be said that without the invention of the wheel, the vehicles of today would never have come into existence.

The oldest wheels are believed to date back to the rollers, or round logs, of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization of 3,500 BC. The subsequent development of wheels joined by an axle, which allowed wheels to rotate, is considered one of the greatest inventions of the human race. Wheels later appeared in Europe and southwest Asia, and it has been established that wheeled vehicles existed in China during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) .

In Japan, a piece of a wooden wheel believed to date from the latter half of the Asuka Period (circa 650) was unearthed at an archaeological site in Sakurai City, Nara Prefecture in 2001. The wheel was made of Japanese evergreen oak, and partial signs of wear indicate that it had been in actual use. The construction of the wheel section provides evidence that wheel production techniques had in fact been developed in Japan by the Asuka Period.

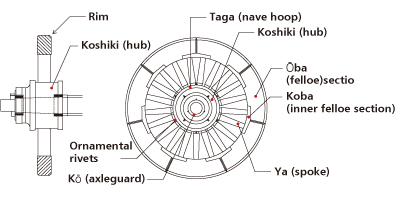

Shigeo Takeda, President of the Takeda Building Contractor's Office, told us that when he heard of the discovery of the wheel fragment, he wasted no time in travelling to the archaeological site to request that he be allowed to attempt a reconstruction of the ancient wheel At the time, Mr. Takeda was engaged in the production of wooden wheels, a business that had been started by his father. "The unearthed section of wheel consisted of an outer portion of the wheel called ōba (the felloe) , along with a spoke section called ya," remembers Mr. Takeda. "Since the construction was almost identical to the wheels that we were producing, I was sure that we would be able to reproduce it." Although Mr. Takeda's wish ultimately remained unfulfilled, this episode demonstrates the depths of his passion towards wheel making.

25 Years of Constructing the Wheels of Gion Festival Hoko Floats, among the Largest Wheels Still in Use in Japan Today

In Kyoto, traditional methods continue to be used in the production of the wooden wheels of Gion Festival hoko floats. These giant wheels, which support hoko parade floats weighing 15 tons, have a diameter of 2 meters and are among the largest wheels still in actual use in Japan today. Looking back on the history of the wheel in Japan, large numbers of wheels were made for the ox-drawn carriages used to transport members of the Heian-era nobility, as is depicted in picture scrolls of the period. These wooden wheels, which had no metal rim, were assembled entirely from wood, with no bolts, nails, or adhesives used. Wheels which do not have a metal rim are liable to wear down from use, and insufficient drying of the wood used to construct them may cause the wheel parts to come apart, making it necessary to retighten wheels or replace worn-out parts.

Takeda Building Contractor's move into wheel production was prompted by its restoration of a hoko parade float. Although wheel production requires techniques entirely different from those used to construct hoko floats, a suggestion that the corporation try its hand at wheel construction spurred the Takeda Building Contractor's Office to learn the necessary techniques, and it was this that marked the beginning of the company's 25-year history of wheel production.

Rims Made of Seven Circle Sections, Each Pierced by Three Spokes Wheels Fashioned Entirely from Wood Native to Japan, and Strengthened Simply through their Assembly

Making Wheels from Naturally Seasoned Wood, using Traditional Techniques of Old

Wheel production begins with the procurement and aging of the wood to be used in construction. The wood is naturally seasoned for 3-5 years, until the desired level of dryness has been achieved. Although artificial seasoning has become more common in recent years, this involves forced heating with high frequency energy, which may result in cracks in the wood. Cracks can prove deadly to a wheel, and even a single cracked piece of wood among the almost 40 pieces that make up a wheel may cause the entire wheel to break. To prevent such cracks from forming, the natural wood seasoning process is of the utmost importance. However, since wood is seasoned over a long period of time, beginning the seasoning process after receiving an order would make it impossible to fulfill the order in a timely manner. For this reason, it is necessary to ensure that seasoned wood is available before beginning a project.

In the wheel production process, the most difficult step is the final joining of the felloes. Most traditional Japanese wooden wheels are made up of 7 felloes along with the inner felloe sections called koba that join these pieces together, 21 supporting spokes, and the central hub called koshiki. Although it is not known why the 360-degree circular rim came to be divided into 7 pieces, considering that 7 is an odd number that is not a divisor of 360, it is a fact that wheels were made in this manner over a period of some 1,500 years.

To determine the angle that divides 360 degrees into 7 equal parts, a sashigane, or carpenter's square, is used. This L-shaped ruler has distance markings on both lengths, as well as on the upper and reverse sides. Japanese sashigane are marked in increments of 1/33 meters, which corresponds to the traditional Japanese measurement of sun, or 3.03 cm. The reverse side of the sashigane is marked in a scale equal to the upper side lengths multiplied by the square root of 2 (1.414) . By using these units to measure the diameter of wood, it is possible to determine the maximum size of square lumber that can be cut out of a round log.

Using techniques such as these, the wheelwrights of old devised a system of wheel assembly based on parts made in sets of seven.

The Roots of the Tire — Found in Production Methods Faithfully Handed Down from the Days of Old

After the days of the ox-drawn carriage of the Heian Era, Japan saw little development of the wheel as a component of wheeled vehicles until the Meiji Period (1868-1912) , when the introduction of Western culture at last brought about a greater expansion of the culture of the wheel. In the time following, the popularization of rickshaws and bicycle-drawn carts gave rise to increased demand for wheels, leading to the establishment of wheel manufacturers throughout Japan.

And now we arrive at the present day. "There used to be several other wheel manufacturers, but now they've all disappeared," says Mr. Takeda. "We must be the only one left in Kyoto." Although wheels with metal rims, added to increase strength, were made for many years, the wheel eventually evolved into the rubber tire. While the wheel did indeed evolve into another form, its fundamentals have become no less relevant, and the importance of its production techniques, faithfully handed down from the days of old, remains undiminished.

During our interview, Mr. Takeda spoke of an automobile manufacturer who visited the Takeda Building Contractor's Office in order to study its wheel production process. Having an understanding of the techniques that have been passed down for over 1,000 years, along with a knowledge of the roots of the wheel, would indeed be a valuable lesson for us all.

Major steps in the wheel production process

Natural seasoning of wood

The wood used to make wheels comes from trees that are about 300 years old and have a diameter of at least 75 centimeters. Initially procured as logs, the wood is cut into pieces measuring 100 x 30 x 21 cm that are then naturally dried for a period of three years or more, with five years considered most ideal. The wheel's central hub is made from the wood of the zelkova tree, while oak is used for the other parts. Oak varieties such as the Japanese evergreen oak are considered most desirable, but with recent shortages in the availability of this wood, Chinese evergreen oak is now often used as a substitute. Recent years have also seen a decrease in large trees satisfying the aforementioned dimensional requirements, making it increasingly difficult to procure the necessary raw materials.

Construction of parts, wheel assembly

Each wheel part is made individually from the naturally seasoned wood. Since all the parts must be positioned at a right angle to the axle, carpenter's tools such as the L-shaped sashigane ruler are used to calculate the proper angle as the parts are being made. After the parts have been completed, they are assembled together. Seven identical arc-shaped segments are joined together using traditional wood joinery methods that make use of no nails or adhesives. Finally, pressure is exerted on the felloes from the outside to the inside, forcing them into the framework. During this step, necessary adjustments to the angle of the spokes are made, and a giant wooden mallet is used to hammer them home. At this time, it is important that the hammering is performed at a right angle to the axle, and care must be taken to avoid using excessive force, for this may cause the spokes to break. However, once the wheel has been put together, the outward force exerted by the compressed spokes stabilizes the inner and outer felloe sections, and unless a portion of the wheel splinters or breaks, the parts will not come unjoined. The Takeda Building Contractor's Office has found ways of optimizing performance that include its development of a specialized hydraulic jack for use in joining parts together, along with an original drilling machine that allows it to drill holes at a right angle to the hub.

Rounding and finishing of wheel

After the wheel parts have been assembled together, the wheel is gradually cut into a round shape. This rounding is accomplished in a manner that involves cutting the four corners off a square to create an octagon, which in turn becomes a sixteen-sided polygon, and continuing to cut the corners in this way. Finally, ornamental rivets are hammered into the wheel, and the wheel is painted. The wheels used for Gion Festival hoko floats weigh about 500 kg each, and, depending on their manner of use, they can last for over 100 years. During this time, any broken parts will be replaced while the wheels continue to be used. It is even said that some float wheels made for the Gion Festival in the early Edo Period (1,600s) continue to be used today. "We can fix just the parts that need fixing, and keep on using the wheels for a very long time," says Mr. Takeda. "That's the great thing about wooden wheels."

Wheel part terminology